Mountain quail are the bird hunter’s ultimate trophy

- Nov 26, 2017

- 4 min read

Updated: Jan 22, 2024

By JIM MATTHEWS

www.OutdoorNewsService.com

Mountain quail are a bird hunter’s ultimate trophy.

I spend at least three of four days a bird season hunting mountain quail, sometime more. I do it not because I think I will actually bring any of our bigger quail home for dinner, I do it precisely because I know it is largely a futile mission.

It is a quest.

I have hunted them most seasons for over 40 years and can count the number I have killed on my fingers and toes – and I don’t need too many of my toes.

Bagging one is like shooting a 30-inch, four-point mule deer.

It is like catching a five-pound brown trout on a dry fly in the Eastern Sierra.

When it happens, there is always a temptation to buy a Lottery ticket or run to a local casino to see how deep this lucky streak runs.

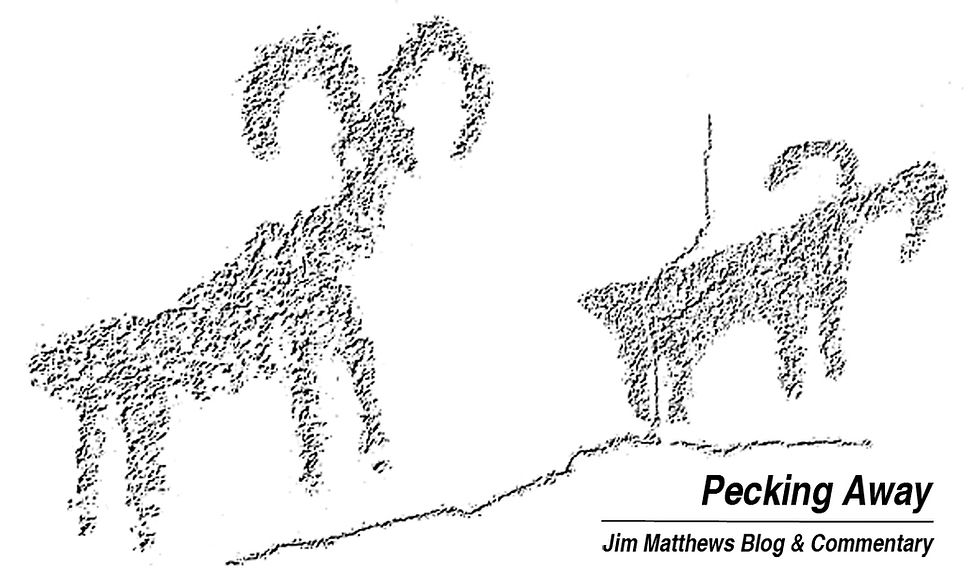

It’s not like mountain quail are rare. Most Southern California residents have them within a few miles of their homes in local national forests where they can be hunted. The big birds live primarily where there is manzanita, from the piñon-juniper and scrub oak habitat elevations up into the tall pines. They live near permanent water sources in these areas. I can take you to a million pull-outs on roads through our public forest, pull over most any mid-morning, and have you cup a hand to your ear and listen carefully. There! Hear that call? That's a mountain quail.

I scout by looking for manzanita and water. Find those two things together, paired with steep canyons, and you will find mountain quail. You will find them everywhere.

Scarcity or remoteness, the elements that define most hunting trophies, are not the issues for mountain quail. Where they live is the challenge.

Most serious mountain quail hunters know they will come back to their vehicles at the end of the day bleeding. For all its beauty, manzanita does that to you if you try to hunt through a patch of it. Those rich, brick-colored branches are really sharpened spring steel. Even when you try to push carefully between two plants, the branches will bend as you put pressure on them, and then snap back to position as you pass. The small branches and stems slash through clothing and skin like a skilled Hollywood movie swordsman with the special effects built-in. The wounds can be so quick and clean, you wonder exactly where you were injured when you discover the bloody gash or puncture.

In the excitement of seeing and chasing after a fleeting glimpse of a mountain quail, a careless hunter will come out sliced into tattered ribbons in typical habitat.

We almost always hear birds in good habitat. Their slow trill, a whistled single note repeated, or the musical “queeee-ark” call that always seems to be given in a place where it echoes through the steep canyons sounding like it was played on a flute and lifted from a symphony. If you are really lucky, you will get close enough to hear the nervous purring notes they make to each other when danger is close.

That close-quarter contact call is what valley and Gambel’s quail hunters hear just before birds start flushing and shooting opportunities usually presented. But that is not the case with mountain quail. They will simply be moving to the far side of the manzanita thicket where they have taken up cover when hearing you coming. When you move around or through the cover (losing blood along the way), the birds will merely circle back under the brush canopy unseen to where you just were standing, purring the whole way.

Days when you actually see one of the long-plumed birds are considered minor victories, even if it is just a glimpse across a canyon as they sprint between shrubs.

Chukar hunters like to joke that you hunt “chukar the first time for sport, and revenge every time after that” because of the ruggedness of the terrain and steepness of the hillsides where they live. But chukar can be hunted and killed consistently once you learn the ropes. It is rocky, but otherwise mostly open terrain. There is no manzanita in chukar country.

If chukar hunters are the masochists of bird hunters, we need to come up with another word to describe mountain quail hunters because it takes masochism to the next level, a higher, Santiago-chasing-windmills level. We endure seasons of patient suffering on the off chance a bird will actually flush through an open spot in a steep thicket of oak brush and manzanita, and then we pray we are facing the right direction and don’t lose our balance as we twist and pirouette, trying to swing the shotgun toward the bird, and then send a load of shot that intersects the path of the quail.

Most hunters simply give up on hunting mountain quail in habitat like Southern California hunters endure. They go back to easier birds.

Like chukar.

Then there are those of us who continue to slam ourselves against those manzanita walls and fall down steep hillsides made slippery with a carpet of oak leaves. We are mountain quail hunters, and even once in a while the bird hunting gods smile and a bird flushes in the perfectly wrong place and it tumbles to the ground in a puff of feathers.

It had been more than five seasons since I’d shot a mountain quail, but this past week one fell to a wonderful old 16-gauge shotgun, a recent gift from a friend, and I again realized why I am enamored with these beautiful, chestnut-flanked quail. The gift from nature was one bird, and it was enough. It was a perfect day.

Mountain quail are a bird hunter’s ultimate trophy.

END

Comments