Wackadoodle group suggests reintroducing grizzly bears back into California wildlands

- Jul 17, 2016

- 5 min read

By JIM MATTHEWS

www.OutdoorNewsService.com

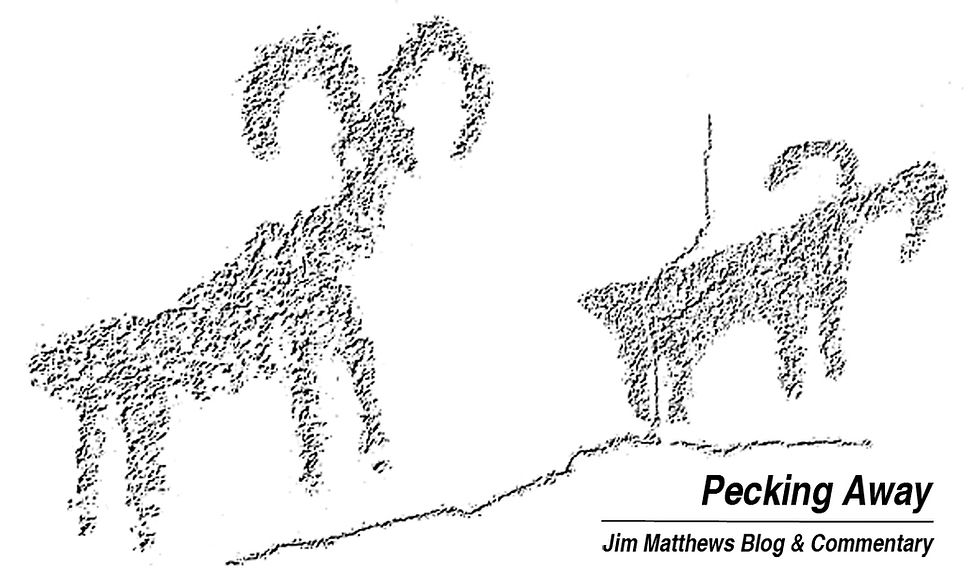

For those of us who love wildlife and the outdoors, but especially students of recent history who understand what the Western states’ wildlife populations looked like in the 1950s, before the Gold Rush, and back into Spanish explorer days, the idea of restoring grizzly bears to California is a beautiful dream.

In the little chunk of pristine scrub-riparian habitat where I take my Labrador retriever to run, I have imagined a day in the not-too-distant past when I might have seen a California grizzly plodding through this habitat moving between feasts of wild elderberries and yucca seed pods. In my mind’s eye, I can see a giant 1,500-pound boar stopping to look at me, his face almost at eye-level with mine. The small hairs on the back of my neck can go up with just the dream of this encounter.

In my mind, I’ve seen these great bears eating acorns under huge, sprawling oaks on the Tejon Ranch. I’ve watched them catching steelhead in a small tributary stream of the Santa Ynez River back when the run of fish was in the 10s of thousands. I’ve seen them on the Carrizo Plain in the spring following around the vast herds of tule elk, searching for elk calves, while grazing on the vast sea of grass.

They are beautiful dreams.

Yet, sensible people also realize that the habitat that once supported grizzly bears in California doesn’t exist any longer in the lonely chunks big enough to support the great bears. We don’t have massive populations of ocean mammals along the coast. We don’t have staggering runs of salmon and steelhead clogging all of our coastal rivers. We don’t have an open Central Valley with vast herds of pronghorn, tule elk, and deer (the estimate was well over a million wild ungulates total when the first missionaries arrived). We don’t have vast tracts of wilderness oak grassland.

Those are the places where the largest grizzly bears on earth lived – our grizzlies. They would feast for days on whale carcasses that washed up on the beach in Monterey. They would snatch salmon out of streams like those photos you see from Alaska. They would feed on acorns unmolested by human gawkers. Today, the whale carcass would be towed offshore so the stink didn’t offend people in town, the salmon run is gone into an irrigation ditch or diverted into your water tap, and the acorn trees are all in the backyards of ranchettes that cover our Sierra and coastal foothills.

Yet, the Center for Biological Diversity recently petitioned the Department of Fish and Wildlife to do a feasibility study to see if grizzly bears could be reintroduced into the state. A similar recent petition to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service was summarily rejected, probably with raucous laughter from the biologists who reviewed the request.

CBD presented a map of vast wilderness areas in the Sierra they thought could support grizzly bears, apparently not realizing that the Sierra was NOT where our grizzly bears lived in this state. Good gracious, did they not even read the wonderful natural history book, “California Grizzly” by Tracy Storer and Lloyd Tevis? The mountains had the leanest pickings for our giants. Bears would visit the mountains seasonally to feed on a specific crop, while traveling, or use them as refuge, but they mostly lived in the valleys and foothills.

So that is the first problem with a grizzly reintroduction: Their habitat and food sources no longer exit. Humans have fragmented and reduced the size of the habitat, and there is no way we can turn the clock back. Any reintroduced bears will face a minefield of problems. The first time a grizzly bear wanders down out of the high country where it was released and finds a fenced pen full of pack llamas, it will think it has died and gone of heaven. You think the reports of a mountain lion killing a goat or a German shepherd and then hauling them off to eat are bad? Wait until you read the first reports of a grizzly bear killing a full pen of llamas – and then refusing to be run off before he finishes his three weeks’ worth of meals. I can see it now when one wanders down out of the Sierra into an almond orchard, climbing into and breaking down the fragile trees by the hundreds as it feasts. Wait until the first mountain biker surprises a grizzly near Mammoth Lakes and gets swatted off the trail with one bone-crushing blow by the startled bear. All these things will happen when we try to shoehorn grizzly bears back into places too small, too lean, and too crowded for these great beasts.

Just as with condors, we would have to set up artificial feeding stations to keep the population healthy and away from humans, livestock, and crops – or face the consequences. The costs would be astronomical. The legal liability in this litigious state would be incredible. If I was that biker, or almond grove owner, or llama packer, the first thing I’d do is sue the state for allowing the bears to be reintroduced and the Center for Biological Diversity for pushing it to happen. They would indeed be culpable.

The second and, for me, bigger problem is that the California grizzly doesn’t exist anywhere in the world. There are no bears we could use for relocations. There are no live specimens in the wild and none even in zoos. The available grizzly bears are all different subspecies – the wrong subspecies for release here.

Apparently we haven’t learned our lesson by introducing the wrong Canadian subspecies of wolf into Yellowstone (another long, different story). Yet, we insist on protecting every subspecies of kangaroo rat because they have unique adaptions and behavior traits that make they uniquely suited to survive in their remnant pockets of habitat. Any relocations are only done with the correct subspecies. However, with megafauna, we have the attitude that “any wolf will do.” We’d have to adopt that same attitude for grizzly bears.

That attitude is wrong scientifically and a disservice to the memory of our extinct bears. Our grizzlies were bigger, they mostly didn’t hibernate, and they evolved to thrive on the most diverse diet of any grizzly subspecies. No bear snatched from Yellowstone or even Kodiak Island would have those traits. I don’t want the wackadoodles to sully up our beautiful dreams of the real California grizzly with some lesser, artificial, inappropriate substitute.

The great California grizzly will live on in our collective memories and imaginations.

END

[Jim Matthews is a syndicated Southern California-based outdoor reporter and columnist. He can be reached via e-mail at odwriter@verizon.net or by phone at 909-887-3444.]

Comments